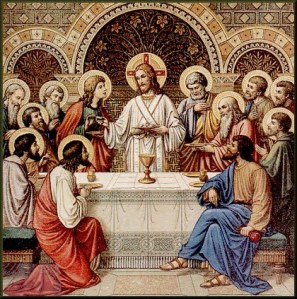

The purpose of this post is to follow up my last one on why the Last Supper was not the First Mass. The next post on Holy Thursday will try to explain exactly what it was: An eschatological banquet enacting a surrogate for sacrifice. But first things first. Four points:

The purpose of this post is to follow up my last one on why the Last Supper was not the First Mass. The next post on Holy Thursday will try to explain exactly what it was: An eschatological banquet enacting a surrogate for sacrifice. But first things first. Four points:

1. A Mass requires the whole Paschal Mystery. The Mass is an anamnetic moment. It is a moment in which the believing community is brought back to the dynamic movement of the Paschal Mystery so as to enter into that moment and imitate the loving self-sacrificial actions of Christ.

Side note: There has been a danger in post-Tridentine theology to speak of the Mass as a re-presentation of the sacrifice of Christ. But this interpretation both fails to take the book of Hebrews seriously and also misunderstands the Jewish concept of “remembrance,” azkarah. Jewish remembrance does not mean that the past event is brought into the present and enacted again. Rather, it means that those who partake in the ritual action are themselves re-presented to the past event. At the Mass, the community of believers becomes present to the Paschal Mystery. Christ is not re-offered or re-presented on the altar of the priest. Rather, the believing community is re-presented to the sacrifice of Christ and, through the power of the Spirit, made part of that self-offering to the Father. Side note over.

The Mass is a memorial of the Paschal mystery. But without that mystery, there could not be a Mass at the Last Supper.

2. A Mass requires the Resurrection. It would only lead to heresy, in my opinion, to posit that when Jesus said at the Last Supper: “This is my body,” the bread became his body. What body did it become? His physical body? That is heretical. His resurrected body? More likely… except the resurrection had not happened yet. Catholic theology has always taken temporality and history very seriously, so I think it is important that we not think that Jesus could somehow offer himself to his disciples in his resurrected form before the resurrection had even taken place!

It would only lead to heresy, in my opinion, to posit that when Jesus said at the Last Supper: “This is my body,” the bread became his body. What body did it become? His physical body? That is heretical. His resurrected body? More likely… except the resurrection had not happened yet. Catholic theology has always taken temporality and history very seriously, so I think it is important that we not think that Jesus could somehow offer himself to his disciples in his resurrected form before the resurrection had even taken place!

3. A Mass requires the sending of the Holy Spirit. Without an Epiclesis, there is no Mass. yet, according to whichever tradition you prefer, the Holy Spirit was not sent until, in John’s gospel, Jesus died and rose, and in Luke’s gospel, until the feast of Pentecost. Either way, while the traditions don’t agree completely with one another, they do agree that Christ sent his Spirit. And that Spirit is the one who transforms both the eucharistic elements and us into the living body and blood of Jesus.

So to summarize thus far, a Mass includes: The Last Supper, Crucifixion, Resurrection, Ascension, Sending of the Spirit. It is a memorial of all those, not just of Jesus’ last meal with his disciples. The Mass we take part in as believers re-presents us to all of the events that took place from Last Supper to Sending of the Spirit. None of those moments are lost in the process. So that last meal was something very important. But it was not a Mass.

So to summarize thus far, a Mass includes: The Last Supper, Crucifixion, Resurrection, Ascension, Sending of the Spirit. It is a memorial of all those, not just of Jesus’ last meal with his disciples. The Mass we take part in as believers re-presents us to all of the events that took place from Last Supper to Sending of the Spirit. None of those moments are lost in the process. So that last meal was something very important. But it was not a Mass.

4. A Mass requires… a Mass. I’m not trying to be snarky here. My point is that, just as we have to be very careful about, say, calling Peter the “first pope,” or the first disciples of Jesus “the first Catholics,” so in a similar way, we should be careful — but even more so, in view of the arguments above — about calling the Last Supper the “first Mass.” The Mass itself took a long time to develop, nor has there ever been one Mass. This second point is very important. There is a reason that there are at least 22 rites in the Catholic Church, including one that does not even have “words of institution.” This is because there has never been one Mass, but only many Masses. Historical critical scholarship, despite its best efforts, has never been able to give us the exact words of Jesus at that Last Supper, and that is almost certainly because it was never remembered in one way. The Last Supper was remembered in different ways in different communities using a variety of words and rituals. As Basil the Great explains to us:

Have any saints left for us in writing the words to be used in the invocation over the Eucharistic bread and the cup of blessing? As everyone knows, we are not content in the liturgy simply to recite the words recorded by St. Paul and the Gospels, but we add other words both before and after, words of great importance for this mystery. We have received these words from unwritten teaching.

There have always been many Masses and many traditions of the words of Jesus. That first generative moment led Jesus into his Passion and sparked many forms of ritualized prayer that we call many rites of the Mass. But that supper never gave us ‘one Mass.’

So what was the Last Supper? That I will discuss on Thursday. In the meantime, let us enter into this week remembering the words of the author of the Gospel of John: “Having loved his own who were it the world, he loved them to the end.” The Last Supper was the beginning of this loving to the end, and it for the sake of learning how to love to the end that we participate in Mass.

I consider your hypothesis incorrect. Jesus did indeed institute all

future Eucharistic celebrations at this His Last Pasch. His words:

“Do this in Remembrance of Me” Confirmed and Ordained His Apostles in priestly and episcopal Holy Orders. To contend otherwise

is an error – or to use your own words – heresy. JM, NY

I think you need to explain the use of such a strong word as heresy – where you are coming from – because I cannot see that in your submission.

Superb. Thank you! I am looking forward to the remainder of your article.

Thanks!

Looking forward to the Holy Thursday article.

Very informative and clear. Again thank you because it makes the Mass more significant and meaningful now that I know more than the lower-case traditions.

There are a lot of slipshod thinking in this piece unfortunately. Just to mention 2 examples: It is not convincing that what is anamnetic in subsequent history cannot be forward looking at its institution. Nor is it reasonable to consider the liturgical developments that gave rise to the rich variety of rites in the Church as a break from the historical event of Jesus’ last supper. Granted this is not a thesis, but if one chooses to write something like this to be more precise in the logic of the thinking.

In the medieval debates over the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception, temporality, as experienced by creation, was considered insurmountable. But we have since learnt, under the guidance of the Holy Spirit, that God is not bound by time. I don’t see how this mystery should be any different.

All very strante. No comment so far about H.H. Francis, SJ.

Peregrinus_sg – could you be more specific?

Catholic theology has always taken temporality and history very seriously….

If the author is to be believed the early Church Fathers were apparently post-Tridentine more than millenium before Trent. Let us not concern ourselves over the mere 3 days between the Last Supper and the Resurrection.

Ghastly HTML problems!

In contrast to the Catechism and orthodox tradition, this blog post is sadly very wooden and, well, jesuitical in the worst sense. Too clever by half, indeed.

Just as each Mass is the Parousia of Christ **in anticipation of His eschatological return in glory**, so the Last Supper instituted the memorial participation in union with Christ’s whole Passion in kenosis. If the Mass cannot occur without the epiclesis, then, by the same (fundamentalist, literalist) logic of this post, forgiveness of sins could not happen without the shedding of blood (Heb 9:22), yet Christ forgave sins before His death on the cross, so, by modus tollens, the Last Supper could and did partake of the Passion even before the historical procession of the Spirit at Pentecost.

Tridentine Canons, session XIII, ch. 1 — “…our Redeemer **instituted this so admirable a sacrament at the last supper**, when, after the blessing of the bread and wine, He testified, in express and clear words, that **He gave them His own very Body, and His own Blood**….”

Council of Trent, DS 1740 — “…because his priesthood was not to end with his death, at the Last Supper “on the night when he was betrayed,” [he wanted] to leave to his beloved spouse the Church a visible sacrifice … **by which the bloody sacrifice which he was to accomplish once for all on the cross would be re-presented**, its memory perpetuated until the end of the world, and its salutary power be applied to the forgiveness of the sins we daily commit.”

CCC 1323 — “**At the Last Supper, on the night he was betrayed, our Savior instituted the Eucharistic sacrifice** of his Body and Blood. This he did **in order to perpetuate the sacrifice of the cross throughout the ages** until he should come again, and so to entrust to his beloved Spouse, the Church, a memorial of his death and resurrection: a sacrament of love, a sign of unity, a bond of charity, a Paschal banquet ‘in which Christ is consumed, the mind is filled with grace, and a pledge of future glory is given to us.'”

CCC 1340 — “**By celebrating the Last Supper** with his apostles in the course of the Passover meal, **Jesus gave the Jewish Passover its definitive meaning.** Jesus’ passing over to his father by **his death and Resurrection, the new Passover, is anticipated in the Supper and celebrated in the Eucharist, which fulfills the Jewish Passover and anticipates the final Passover** of the Church in the glory of the kingdom.””

CCC 1350 “[When] the bread and wine are brought to the altar; they will be offered by the priest in the name of Christ in the Eucharistic sacrifice in which they will become his body and blood. **It is the very action of Christ at the Last Supper – “taking the bread and a cup.”**

I Cor 13 — 23 “For I received from the Lord what I also passed on to you: The Lord Jesus, on the night he was betrayed, took bread, 24 and when he had given thanks, he broke it and said, “This is my body, which is for you; do this in remembrance of me.” 25 In the same way, after supper he took the cup, saying, “This cup **is** the new covenant **in my blood**; do this, whenever you drink it, in remembrance of me.” 26 For whenever you eat this bread and drink this cup, you **proclaim the Lord’s death until he comes.**”

Note that Christ says at the Last Supper that this IS (not will be!) His Body and Blood. His entire life was an offering in the Spirit to the Father. His Passion had begun even before its consummation on the Cross. The Last Supper established the covenant IN HIS BLOOD even before He shed it on the Cross. This proleptic participation enjoyed by the Apostles is mirrored in our amamnetic participation of it after the fact.

Luke 22 — 14 **When the hour came**, Jesus and his apostles reclined at the table. 15 And he said to them, “I have eagerly desired to eat **this Passover with you before I suffer.** 16 For I tell you, **I will not eat it again until it finds fulfillment in the kingdom of God.”** 17 After taking the cup, **he gave thanks** and said, “Take this and divide it among you. 18 For I tell you I will not drink **again** from the fruit of the vine until the kingdom of God comes.”

The hour of redemption had come, and in that kairos Christ established His sacrament of life, the Eucharist–the Thanksgiving for Grace (“he gave thanks” εὐχαριστήσας!). Christ emphasizes the proleptic nature of the participation (desired, again until, fulfillment, etc.). He also connects the unity (“this [unified-singular] Passover”, “it [the very same]”) of the Last Supper Pascha with the Pentecostal fulfillment in the Spirit. It is a profound but beautiful detail and irreformable pattern for the Church–indeed, it is the very essence of the Church!–that Christ freely gave Himself to His Apostles AT THE LAST SUPPER BEFORE He gave Himself to the Father and to the world on the Cross. For it was by first entrusting Himself to them sacramentally that their faithful communion with Him, and their priestly mediation for Him, could be, and was, drawn up into His one sacrifice on the Cross and ultimately made into a global mission at Pentecost.

I believe I am not alone in thinking this post is a sophistical blight on the Easter season.

Not a lot of charity there!

Are you, perchance, on commission as an apologist for this blog, or just for this post? I have replied to the substance of O’Halloran’s post. Care to do the same with my reply?

I merely ask for clarification – nothing more, nothing less.

In any case, for the sake of clarity and brevity, I reduced the dispute to a disjunctive syllogism on my own blog (where I edited these comments into a more polished essay type thingamajig):

If

1) the Eucharist was established at the Last Supper, which I think is indubitable according to orthodox Catholic tradition, and if

2) the Mass just is the historically concrete celebration and participation in the Eucharist by Christians, then it follows that either

3a) the Mass now is sacramentally unified with the Eucharist as celebrated at the Last Supper or

3b) the Mass now is not sacramentally united with the institution of the Eucharist at the Last Supper.

4a) If the former, then the Last Supper was indeed the first Mass in so far as the Mass just is the communion of the faithful with the Body and Blood of Christ.

4b) If the latter, however, as O’Halloran argues, then Christianity is a Gnostic event that can only be accessed by secrets, lost in the jumble of critical history, rather than by sacraments, which are revealed to the masses by the scriptural tradition.

By the way, St. Thomas addresses the issue of what body Christ gave at the Last Supper even prior to the Resurrection (ST III, q. 81, esp. a. 1 & 3): http://www.newadvent.org/summa/4081.htm

Consider also St. Thomas’ discussion of a similar problem vis-à-vis baptism in ST III, q. 66, a. 2. As you read, replace the word “baptism” with “the Eucharist”:

Objection 1. It seems that Baptism was instituted after Christ’s Passion. For the cause precedes the effect. Now Christ’s Passion operates in the sacraments of the New Law. Therefore Christ’s Passion precedes the institution of the sacraments of the New Law….

Objection 2. Further, the sacraments of the New Law derive their efficacy from the mandate of Christ. But Christ gave the disciples the mandate of Baptism after His Passion and Resurrection…. Therefore it seems that Baptism was instituted after Christ’s Passion. …

On the contrary, Augustine says in a sermon on the Epiphany (Append. Serm., clxxxv): “As soon as Christ was plunged into the waters, the waters washed away the sins of all.” But this was before Christ’s Passion. Therefore Baptism was instituted before Christ’s Passion.

… [S]acraments derive from their institution the power of conferring grace. Wherefore it seems that a sacrament is then instituted, when it receives the power of producing its effect. … But the obligation of receiving this sacrament was proclaimed to mankind after the Passion and Resurrection. First, because Christ’s Passion put an end to the figurative sacraments, which were supplanted by Baptism and the other sacraments of the New Law. Secondly, because by Baptism man is “made conformable” to Christ’s Passion and Resurrection, in so far as he dies to sin and begins to live anew unto righteousness. Consequently it behooved Christ to suffer and to rise again, before proclaiming to man his obligation of conforming himself to Christ’s Death and Resurrection.

Reply to Objection 1. Even before Christ’s Passion, Baptism, inasmuch as it foreshadowed it, derived its efficacy therefrom; but not in the same way as the sacraments of the Old Law. For these were mere figures: whereas Baptism derived the power of justifying from Christ Himself, to Whose power the Passion itself owed its saving virtue.

Consider also ST III, q. 83, a. 4 ad 9:

“[F]rom this the mass derives its name [missa]; because the priest sends [mittit] his prayers up to God through the angel, as the people do through the priest. Or else because Christ is the victim sent [missa] to us: accordingly the deacon on festival days “dismisses” the people at the end of the mass, by saying: “Ite, missa est,” that is, the victim has been sent [missa est] to God through the angel, so that it may be accepted by God.”

Insofar as Christ ‘sent’ Himself to the disciples and Himself to the Father in “giving thanks” at the Last Supper (cf. Luke 22:14ff), He manifestly celebrated the first Holy Mass at the Last Supper.

I would also like to address your historical-critical point about the disunity of the Mass, with––surprise!––another teaching from St. Thomas (ST III, q. 64, a. 2 ad 2):

“Objection 1. It seems that the sacraments are not instituted by God alone. For those things which God has instituted are delivered to us in Holy Scripture. But in the sacraments certain [historically diverse] things are done which are nowhere mentioned in Holy Scripture; for instance, the chrism with which men are confirmed, the oil with which priests are anointed, and many others, both words and actions, which we employ in the sacraments. Therefore the sacraments were not instituted by God alone. …

“[However,] the sacraments are instrumental causes of spiritual effects. Now an instrument has its power from the principal agent. But an agent in respect of a sacrament is twofold; viz. he who institutes the sacraments, and he who [in the Holy Mass] makes use of the sacrament instituted [viz. the Eucharist], by applying it for the production of the effect [viz. as the Holy Mass]. Now the power of a sacrament cannot be from him who makes use of the sacrament: because he works but as a minister. Consequently, it follows that the power of the sacrament is from the institutor of the sacrament. Since, therefore, the power of the sacrament is from God alone, it follows that God alone can institute the sacraments.

“Reply to Objection 1. [Historical diverse human] institutions observed in the sacraments are not essential to the sacrament; but belong to the solemnity which is added to the sacraments in order to arouse devotion and reverence in the recipients. But those things that are essential to the sacrament, are instituted by Christ Himself, Who is God and man. And though they are not all handed down by the Scriptures, yet the Church holds them from the intimate tradition of the apostles….”

By the way, I don’t mean to pick a fight, I’m just being forthright that this post struck both a nerve and a chord with me. I highly commend this passage from your post:

“At the Mass, the community of believers becomes present to the Paschal Mystery. Christ is not re-offered or re-presented on the altar of the priest. Rather, the believing community is re-presented to the sacrifice of Christ and, through the power of the Spirit, made part of that self-offering to the Father.”

That’s beautiful. Have you read Fr. Keefe’s Covenantal Theology? That book truly changed my life as a Catholic, and some of this post reminds me a lot of Keefe’s work.

Now, the reason I chafe against bifurcating the Mass from the Eucharist is, paradoxically, for the same reason you object to referring to “one Mass”. Effectively you are arguing that a proper Mass must contain all the right elements––Pascha, Epiclesis, Resurrection, etc.––to count as a Mass, yet you also say there is no unified core or essential elements in the so to speak “Mass effect”! Even granting your minimalist theory of what the Mass is, it still means that all Christians’ historically diverse “Mass efforts” (the Liturgy is the work of the people, after all!) are mystically one with the mysteries celebrated in them WHICH INCLUDES regeneration in Baptism (cf. again ST III, q. 66, a. 2), life in the Eucharist (as instituted at the Last Supper), the Resurrection as the proleptic promise which illuminates and vindicates all the temporally prior mysteries.

Finally, I called this post, indelicately, I admit, a “blight” because, to speak even more bluntly, it struck me as a somewhat pretentious “bonerkiller” right before Easter.

I for one am just wanting to understand your comments a little more clearly – to which end, thank you for additional responses – I don’t think anyone would suspect you of wanting to pick a fight, just open and honest debate.

However, as a sensitive Englishman, ( a very rare admittance ), I do find expressions such as ‘pretentious bonerkiller’ a tad uncharitable, right before Easter.

You’re absolutely right, graywills, my verbiage was uncouth and out of place, and I sincerely apologize to the hosts and readers here. Using “buzzkill” would have been as effective. I did, however, wait until after Easter to write here.

I openly admit that this post is very disturbing to me, and it obviously elicited a strong emotional response, though one I believe I mostly successfully tempered with clear and well supported points. I converted to the Faith nearly a decade ago, and it was the Eucharist––Christ given to us in order to give us to the Father––that brought me in. Hence, I have a mother bear’s sensitivity to perceived threats against the Eucharist. As Fr. Keefe’s work shows, the Catholic Church JUST IS the Eucharistic communion. Anything that jeopardizes that joyful mystery is not just ‘post-Tridentine’, not merely ‘quasi-Catholic’, but in fact anti-Catholic at the most basic level.

Now, I retracted one rude word earlier, but I still maintain that this post has a pretentious air about it. It’s not titled “Was the Last Meal the first Mass?” but is a blunt assertion that the negative is true. Why, right before Easter, shock faithful readers with such an assertion?

If the first Mass wasn’t at the Last Supper, then when was it? After the Resurrection, when the Scriptures plainly state they (the disciples) “knew Him in *the* breaking of *the* bread” (Lk 24:28–35 ἐγνώσθη αὐτοῖς ἐν τῇ κλάσει τοῦ ἄρτου), a blatant reference to the Eucharist? O’Halloran wouldn’t countenance that since the Spirit had not descended yet.

Well, how about just before Pentecost, when the Scriptures state that the faithful were “of one accord devoted to *the* prayers [τῇ προσευχῇ; Acts 1:14, cf. also Acts 2:1]”? (Why “the prayers”? Because that’s a reference to the received Eucharistic prayers in the primeval Church! Cf. again Luke 24:35.) The emphasis of the Spirit’s descent is on EVANGELISM, not on WORSHIP (cf. Acts 1:8, 2:4–5, 2:14ff.), so O’Halloran is being sloppy on that point; the Church received the Spirit *for evangelistic power* (cf. Ac 1:8, Lk 24:49) after it had been a Eucharistic fellowship from Christ’s Passion. Even if we agree that they couldn’t have celebrated “the Mass” without the Spirit, John 20:21–23 says Christ gave the disciples the Spirit shortly after His Resurrection, so EVEN IF we grant that the Last Supper was not a complete first Mass, there is no basis for saying there couldn’t be a Mass prior to Pentecost.

As my syllogism above shows, the thesis of this post is a direct threat to the ontological continuity of the Catholic Church. It is no coincidence that Maundy Thursday BEGINS the Triduum, just as it began Christ’s Passion. If we are made present to the Resurrection on Easter, and to the Cross on Good Friday, on Maundy Thursday we are also immersed into the Eucharistic foundation Christ laid at the Last Supper.

Further, while I truly value and try to practice the Ignatian policy of reading other charitably, though my reaction may have fallen short of charity, I can’t help but detect a troubling subtext behind O’Halloran’s thesis. His denigration of the sacrificial (dare I even say propitiatory?) meaning of the Eucharist is all of a piece with ‘modern’, ‘nouvelle’, ‘post-Tridentine’ sacramental theology of the past few decades (cf. e.g. Tad Guzie, SJ’s, 1974 Jesus and the Eucharist). Notice, indeed, how this post is but one link in a larger chain of reasoning, presumably one that points to a radically de-sacralized, perhaps even theoretically female, priesthood. I’d be delighted to find out that I’m wrong about O’Halloran’s sacramental Tendenz, but the fact that he’s also a contributor to Vox Nova further triggers my Catholic “Spidey sense”.

Nathan, two thoughts: first, Saint Thomas’s explanation in the Summa III 81 iii is very good in explaining what type of presence was given at the Last Supper. Secondly, there is no rite in the Catholic Church that does not have the words of institution. The anaphora of Addai and Mari, when used by those in communion with Rome, inserts the words of institution, which they have always done. It does not have those words when said by those not in communion with Rome, and as Ansgar Santogrossi showed in Nova et Vetera in 2012, the document from the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity, which is not a Magisterial document, contradicts a number of higher more binding Magisterial documents on the question. The article is well-worth the read.

Thanks, I’ll look into the article you recommended. As for Aquinas, while clear, I don’t think his methodology is adequate. I think more modern methods of interpreting scripture can and should be fruitfully brought to bear on this question.

Just before every consecration it is stated … “In a similar way, when SUPPER WAS ENDED, he took the cup …”

This states clearly that the Mass occurred after the Last Supper. In the writings of the great mystics (e.g. Maria of Agreda and others), this is confirmed. The low table around which they had the last supper was removed. An altar was brought in and Jesus taught these Bishops how to celebrate the Mass.